In the spring of 1974, members of the College’s social committee meet to plan its concerts and dances for the fall term.

Homecoming is the marquee event, and working with a limited budget, students are determined to bring in a notable performer.

Following a spirited debate, the choice is down to two performers: Bruce Springsteen and Billy Joel.

A relatively unknown Jersey rocker, Springsteen is hailed as the new Dylan. He is touring in support of his second album, “The Wild, The Innocent, and the E Street Shuffle.”

Meanwhile, Joel finds success with the title track of his second album, “Piano Man,” his first top 20 single and first gold album.

The committee’s budget is $10,000 for the academic year. Springsteen would cost $3,000; Joel, $4,000.

“We can’t risk being wrong here,” is the sentiment of those who believe Springsteen is still too obscure to book. “Let’s go with Billy Joel.”

Even Columbia Records, which signed both singers, has their own debate on which singer to support for radio airplay.

“One promotion man went around the country telling the few stations that played ‘The Wild, The Innocent, and the E Street Shuffle’ to take it off the air and add Billy Joel’s new album instead,” writes Springsteen biographer Dave Marsh in his book, “Bruce Springsteen on Tour: 1968-2005.”

As chair of the social committee, Chris Fink ’75 has final say. He and some other committee members also work at WRUC, the campus radio station. As such, they are privy to an advance copy of “The Wild, The Innocent, and the E Street Shuffle” before its release the previous September. Fink knows which way he is leaning.

“When we heard that, we said holy smokes, this guy is going to reinvent what we know,” he recalls. “We have to get this guy.”

The decision to go with Springsteen proves prescient. Around the same time the committee chooses Springsteen, music critic Jon Landau sees the singer when he opens for Bonnie Raitt at Cambridge's Harvard Square Theatre on May 9, 1974. In an essay for a Boston-area alternative weekly newspaper, Landau, who would soon become Springsteen’s manager, authors the three most famous sentences of a rock review:

“Last Thursday at Harvard Square, I saw my rock and roll past flash before my eyes,” Landau writes. “And I saw something else: I saw rock and roll future and its name is Bruce Springsteen. And on a night when I needed to feel young, he made me feel like I was hearing music for the very first time.”

The review instantly raises Springsteen’s profile, which is problematic for Union. The singer’s representatives insist on renegotiating its contract with the College. The asking price jumps to $10,000. The College’s booking agency and Fink stand firm, though.

The show will go on.

The concert is scheduled for Oct. 19, 1974, at 9 p.m. in the intimate Memorial Chapel. Tickets, normally a dollar or so, are $2.50. Fink wants to at least break even.

Built in 1925, the chapel has hosted everything from signature College events like Founders Day to literary readings. Rock concerts have a mixed record, due to the physical damage to the building and trash left behind. In 1958, President Carter Davidson threatened to ban concerts because of the smoking and drinking associated with them, according to the Encyclopedia of Union College History, and in 1965, a college official denied the sophomore class permission to have a rock concert there because it did not represent “the standards of the College.” The decision was overruled a week later, but by 1982, “hard rock” concerts were banned in the Chapel.

Hours before they take the stage, Springsteen and his band (which now includes new members keyboardist Roy Bittan and drummer Max Weinberg) perform a routine soundcheck. The sound is so intense, it knocks out power to the building. Organizers scramble to place emergency generators out back of the chapel in time for the show.

Meanwhile, Fink is in the balcony, helping with lighting and other issues. As the soundcheck continues, he notices pieces of debris falling from the ceiling. Mindful of the warning he received from higher-ups about protecting the chapel, he yells down to Springsteen’s handlers to turn down the volume. They ignore him at first.

Desperate, he pulls from his pocket the band’s $3,000 check for payment and waves it over his head.

“Turn it down or there is no show,” he tells them. Reluctantly, they comply.

As showtime approaches, throngs of people descend on the chapel. Many are from outside the Union community. Word has spread that Springsteen is on campus. Fink stations extra volunteers at the doors to control the lines. The venue only holds about 1,000 people. It fills fast. Hundreds of people camp outside on the lawn.

“We need to open every window so people outside can hear,” Fink says.

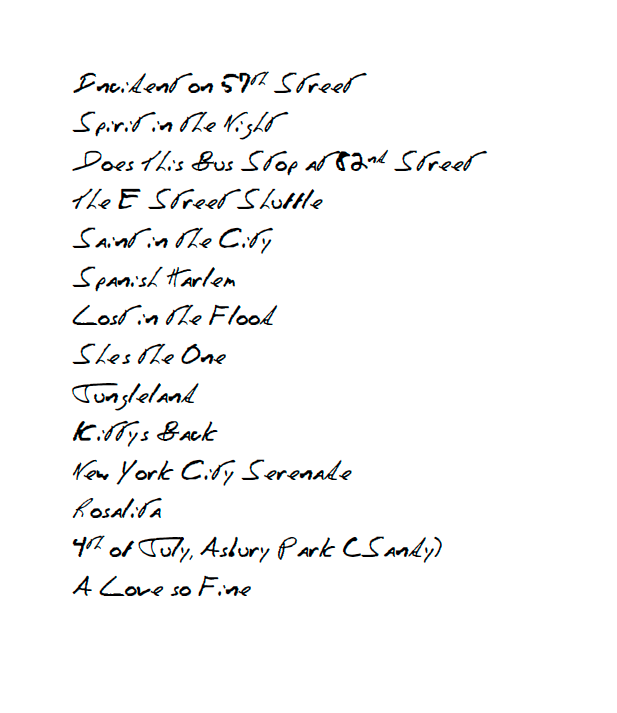

The warmup act, a local group named Goebel and Lang, plays for an hour before Springsteen and his band take the stage. He opens the 14-song set with a haunting “Incident on 57th Street” and closes with a bouncy cover of the Chiffons “A Love So Fine.” The powerful, noisy show features most of the tracks from “The Wild, the Innocent and the E Street Shuffle.” Springsteen also performs two new songs that will appear on his breakthrough album “Born to Run” nearly a year later, a 12-minute version of “Jungleland” featuring different lyrics from the album version and “She’s the One.”

When the concert ends, the crowd roars appreciatively for what they have witnessed for just over two hours. The signature shouts of “Bruuuce!” that have punctuated his concerts for decades had not materialized yet.

“It was just an unbelievable performance,” Fink, now retired but an active volunteer in Asheville, N.C. economic development and community health care, recalled recently. “The whole energy of the show. He just blew us away. People filed out of the chapel almost quietly, as if they knew they had experienced something they had never seen before. It was like, wow, I think I just saw something special.”

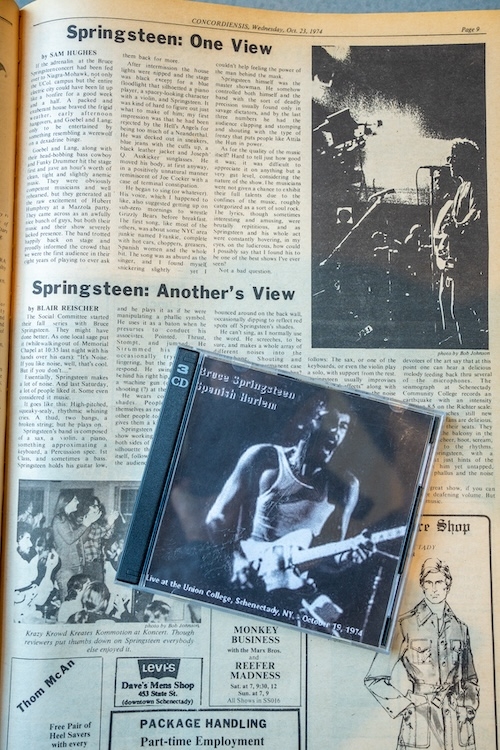

Two separate reviews in the Concordiensis, the student newspaper, were mixed. “It’s a great show, if you can stand the deafening volume. But it ain’t music,” writes one reviewer. “They say that one should listen to the lyrics. I find it hard to believe that there are any.”

Describing Springsteen as a “werewolf on a dexadrine binge” another reviewer, Sam Hughes ’76 writes that by the last three numbers, Springsteen “had the audience clapping and stomping and shouting with the type of frenzy that puts people like Attila the Hun in power.”

More than his bombastic prose, Hughes would later regret that he held back on his enthusiasm in a 2010 essay for Union’s alumni magazine but reaffirm his sentiment about the show, writing, “to this day it remains one of the more amazing musical and theatrical performances I’ve ever witnessed.”

A few years ago, the Times Union asked readers for their memories of the show.

“We sat in the balcony, directly over the stage, and looked down into Clarence's saxophone, and we were in heaven,” said one. “What a show. The crowd went away deliriously happy and spread the word far and wide that this was going to be the band.”

Recalled another, who went with his girlfriend, a student at Union: “I was totally blown away by the show. I started telling all my friends about this amazing artist who was destined for major stardom.”

Perhaps no one captured the memorable show than this attendee: “Without a doubt, my favorite Springsteen show. ... It's like your first kiss.'”

Unfortunately, there is little memorabilia to commemorate the show. No ticket stubs or posters promoting the event have surfaced. A few grainy photos appeared in the Concordy and The Garnet Yearbook, but little else. Bootlegs of the show, including “Spanish Harlem,” aptly named for the Ben E. King classic Springsteen performed that night, and “New York City Serenade” remain popular with collectors.

Springsteen’s appearance at Union came at a critical time for the College. Thomas Bonner had just been inaugurated as the College’s 15th president. Also, plans were announced for a new hockey facility on campus, Achilles Rink (later to be renamed Messa Rink).

Springsteen turned 75 last month. Both he and Billy Joel are members of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and continue to tour.

Fink is helping the Class of 1975 plan its 50th ReUnion for next spring. The debate over whether Joel would have been the safer choice ended on the night of Oct. 19, 1974.

A year later, Springsteen appears simultaneously on the covers of Time (“Rock’s New Sensation”) and Newsweek (“Making of a Rock Star”) magazines, the first rock star to land on the cover of both in the same week.

“Springsteen was a culmination, it was not a coincidence,” said Fink. “Springsteen on campus was the result of two terms of incredibly hard work by a social committee that was lucky enough to have a team of talented, resourceful volunteers willing to take the risk.

“As it is now 50 years out and we're still talking about this, it's fair to say that in the end, our foresight was vindicated.”